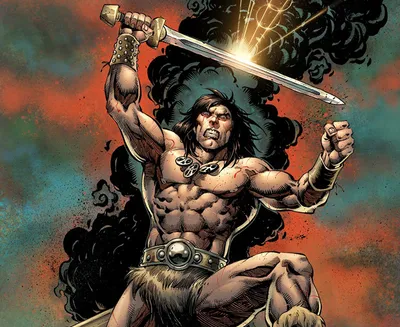

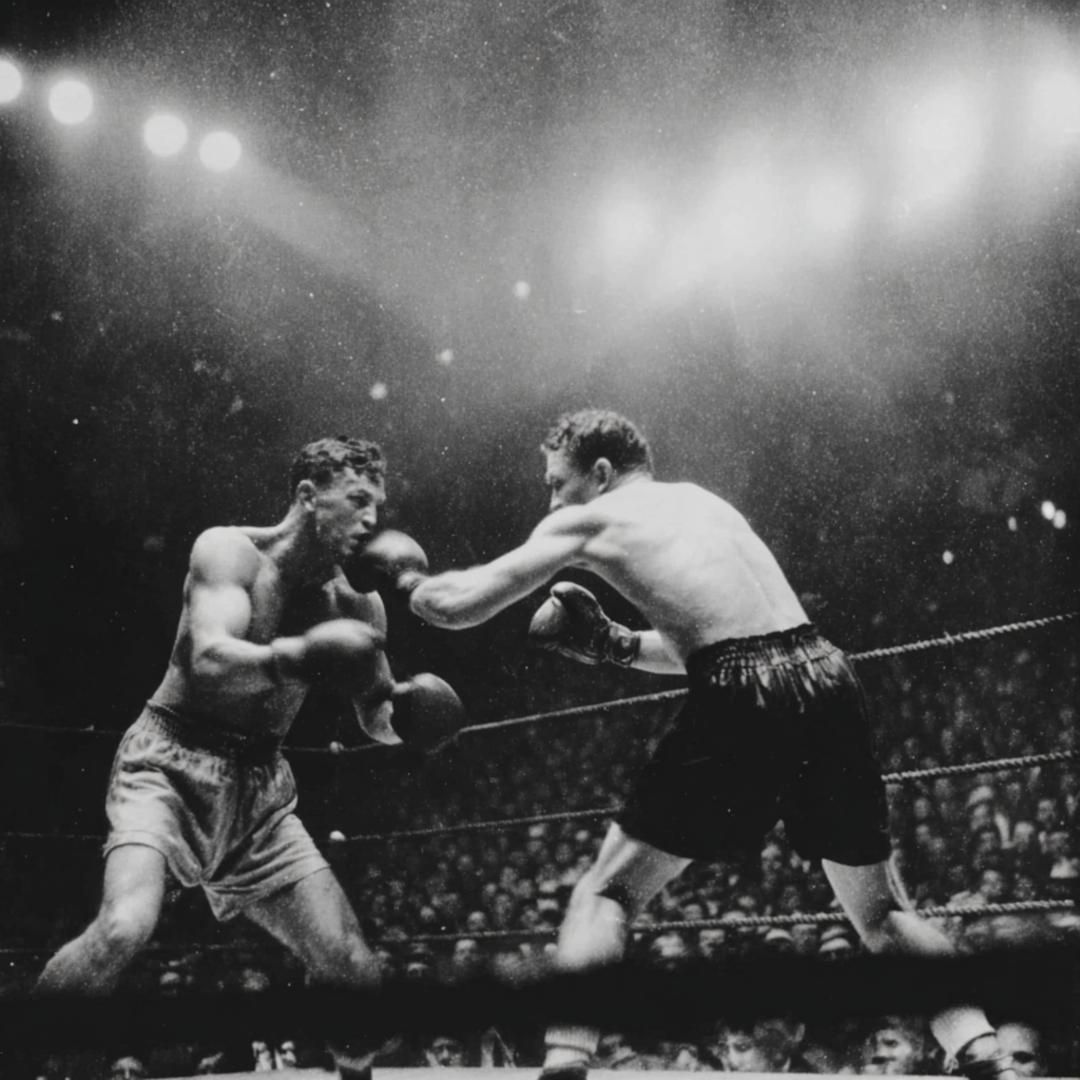

SCHMELING had imitated Jack Dempsey's style. He fought out of a sort of crouch, but wasn't able to bob and weave as the old Mauler did. The style seemed suited to him, but it wasn't developed. His handlers wanted to turn him into a more upright fighter. Not immediately. Against Paulino, the crouch was still in evidence, but while training for Sharkey it was almost entirely abandoned. There has been too much puttering and tinkering with Schmeling. He is essentially a fighter and not a boxer. He should be made to fight and not box. Sharkey has forgotten more about the mechanics of fisticuffs than Schmeling will ever know. But skill, of course, isn't essential in the winning of a heavyweight championship. Sullivan, Jeffries and Dempsey proved that. But, without boxing ability, you must have ruggedness, aggressiveness and a real punch. With the punch must go not only power but accuracy. Max's next fight was with Paulino. He won the decision in fifteen rounds, giving the Basque a terrible beating in the last five, a beating that turned Paulino into a bloody and mangled object. But again the same objections found in the Risko fight held good here. For the first ten rounds it was a miserable exhibition, with the men standing off to beat and pawing away without doing much damage. In short, it took two-thirds of the fight for Max to find how to penetrate the burly Spaniard's awkward guard. That doesn't seem to me an indication of exceeding smartness.

Still, the interest in foreign fighters, and particularly the fact that Schmeling was the first championship contender to come out of Germany, helped push him along rapidly. He has color and an interesting style, and his marked physical resemblance to Dempsey—aside from his style—added to the publicity that was given him. Had he kept in harness after his fight with Paulino, the Teuton might have proved considerably. But trouble with Arthur Bülow, his former manager, interfered with his return home. He didn't want to fight because Bülow held a contract that permitted him to collect one-third of Schmeling's earnings. So instead of boxing regularly, Max took to the gymnasiums and vaudeville theatres of Germany. That year of comparative idleness didn't do him any good. I have said frequently that a boxer must fight to keep in proper shape. All the sparring practice in the world can't take the place of a few keenly contested bouts for getting a man in real trim. Schmeling didn't have those fights, and he did himself a lot of harm by his abstinence.

Still, his knockout victory over Risko brought him continued praise. Most of the boxing writers thought that John was washed up physically, but his fine fights with Von Porat, Campolo and others proved that this was not true. So Schmeling's triumph began to assume greater and greater proportions. Eventually, Max was recognized as the leading contender for the title Gene Tunney had left vacant. The New York State Athletic Commission rescinded the ban it had placed on him for refusing a scheduled match with Phil Scott and decided to recognize the winner of a Sharkey-Schmeling bout as heavyweight champion of the world. It seems rather extraordinary, when you stop to think of it, that a man who had really accomplished so little should have been given that opportunity. There were two reasons of course—the lack of good big men and the fact that Schmeling was the best fighter in Europe.

I WATCHED the Black Uhlan very carefully in training. As a man who has conditioned fighters for forty years, I think I can see what the average observer misses. Max was badly trained. He did little road work, no bag punching and much less boxing than he should have done. I imagine the automobile accident he suffered in Europe harmed his legs, and it was felt that too much road work would do him no good. People who know what must be done to get a fighter in shape understand that a training period without lots of road work is so much wasted time.